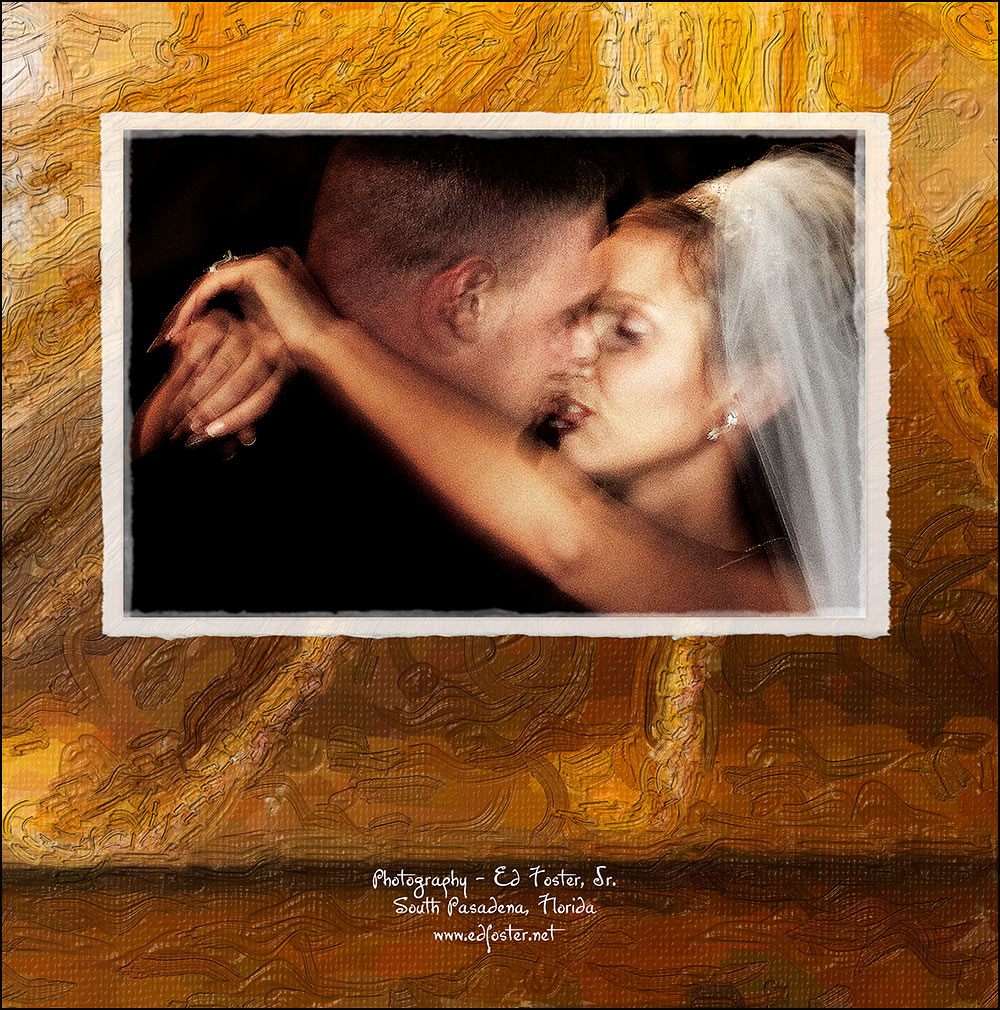

Posted by: Ed Foster Jr.

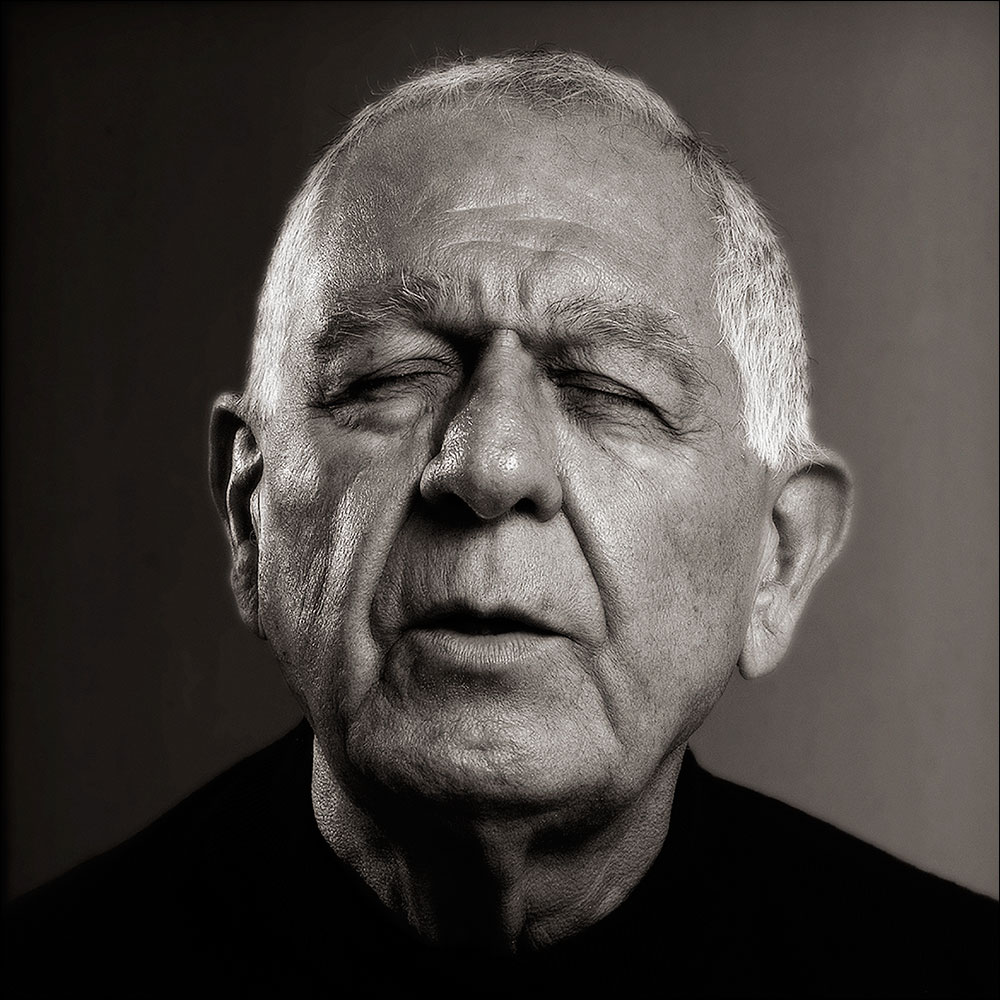

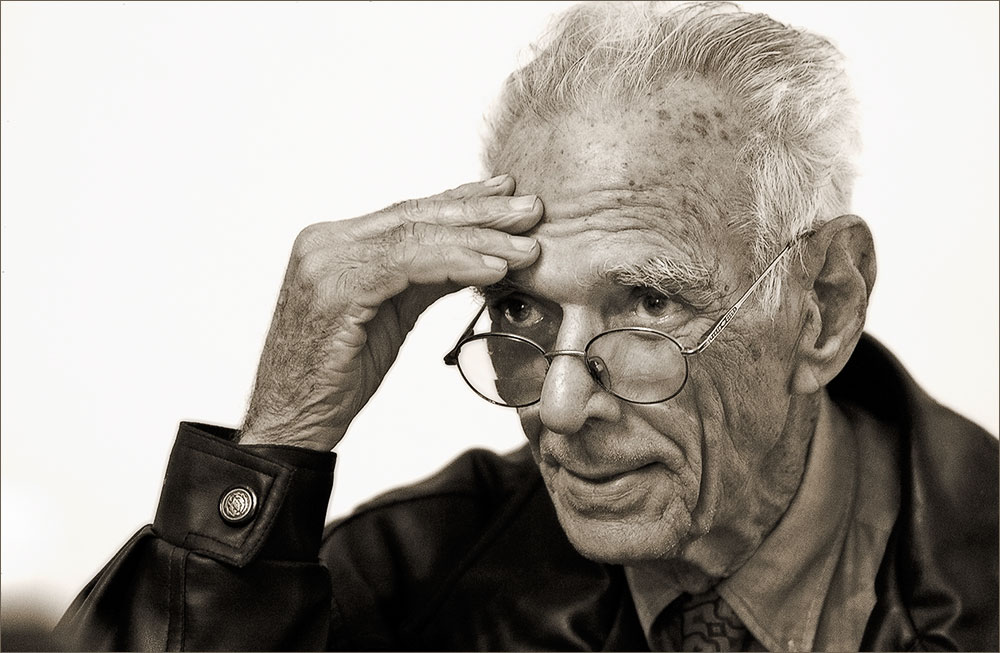

There are two subjects that really spark a fire in the eyes of Patricia Rodríguez Alomá. One is Habana Vieja (Old Havana) in Cuba, and the other is her nonagenarian father, Dr. Rubén Rodríguez Gavaldá. They are both a part of her heritage and her awe.

Patricia is the Director of Planning with the Office of the Historian of Old Havana, the Cuban government office responsible for the ongoing social and physical transformation of a once blighted neighborhood into a UNESCO World Heritage Site. She is also her father’s daughter who inherited the doctor’s enthusiasm and tireless work ethic.

During one of my meetings with the forty-something architect to learn about the work of the Historian’s Office, she struck a parallel to the usefulness of some of the aged buildings she helps resurrect with the active and productive life of her 90-year-old father. Patricia is not one to tell her guests about how buildings and lives were transformed in Habana Vieja. Her lessons quickly become long walking tours, and so it was with her father when she proposed an introduction.

The air was quite cool on that January morning in 2005 as I peered through the arched portal of Convento de Brigida in Old Havana waiting for the couple to arrive. Within minutes I spotted Patricia’s red mane in the distance as she and her father briskly strolled arm-in-arm along Calle Brasil.

“If that’s her dad,” I thought, “he certainly doesn’t appear to have been around for nine decades.”

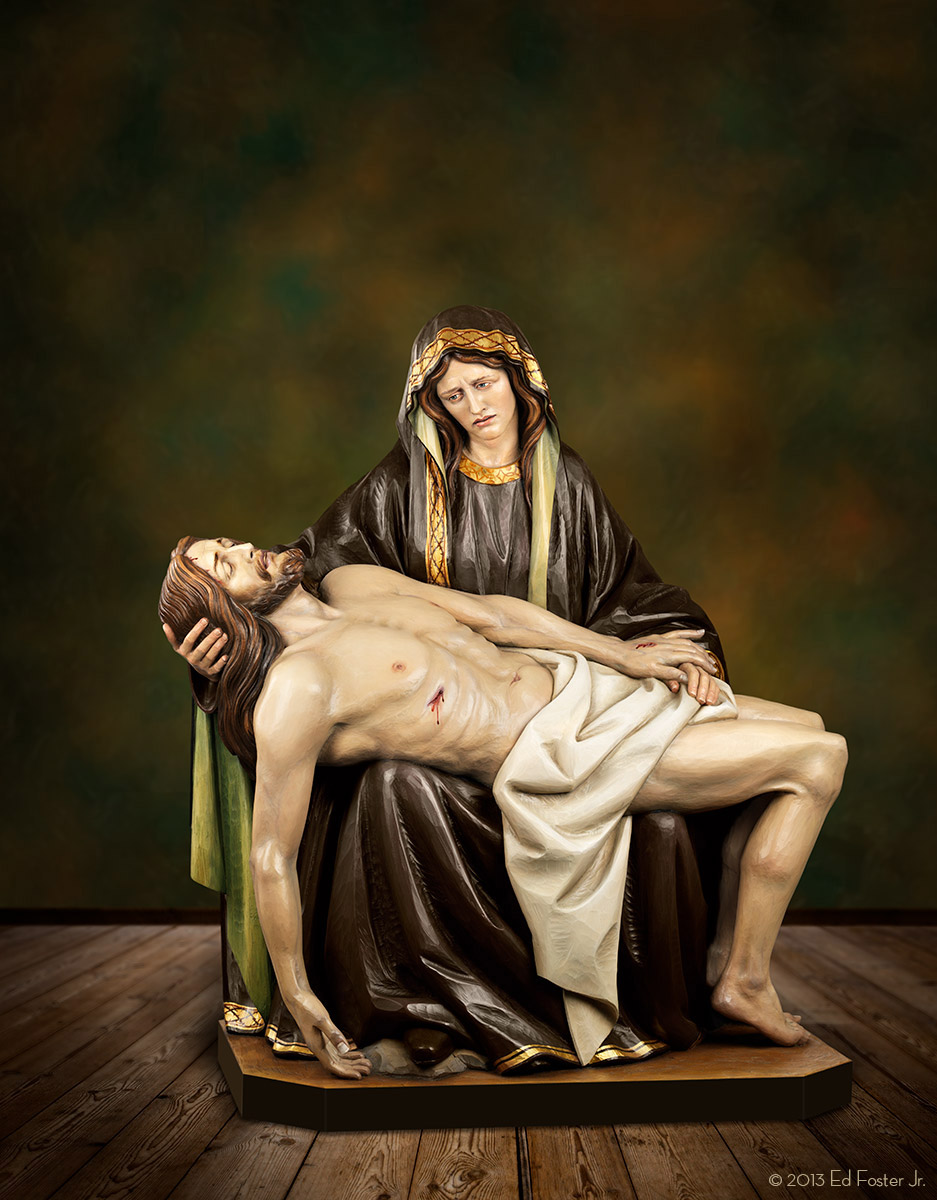

After introductions were made, two of the hospitable Sisters of St. Bridgid served coffee and cookies in the cozy dining room of the convent. Whether or not it was the presence of the nuns or my colleagues, Dr. Rodríguez Gavaldá must have felt compelled to share his religious beliefs.

“I am agnostic and really don’t identify with any religion. I respect religious people very much and I respect you”, he told my companions, “because it comes from the integrity of your heart. I try to live a moral life and believe in charity for all and malice to none,” he said as he repeated his creed in English as well as Spanish.

With that behind him, he stressed the need for allergy specialists in Cuba and then began using medical terms thay I didn’t fully understand. Some of my companions who are medical professionals seemed to lean on every word as if they were in a classroom. I surmised from his gusto and their attentiveness, the aged pediatrician was right at home.

His impromptu lecture continued for nearly one hour and no question went unanswered.

Dr. Rodríguez Gavaldá reluctantly spoke about himself and his place in the history of research, education and the treatment of immunological diseases in a country where hypersensitivities are prevalent.

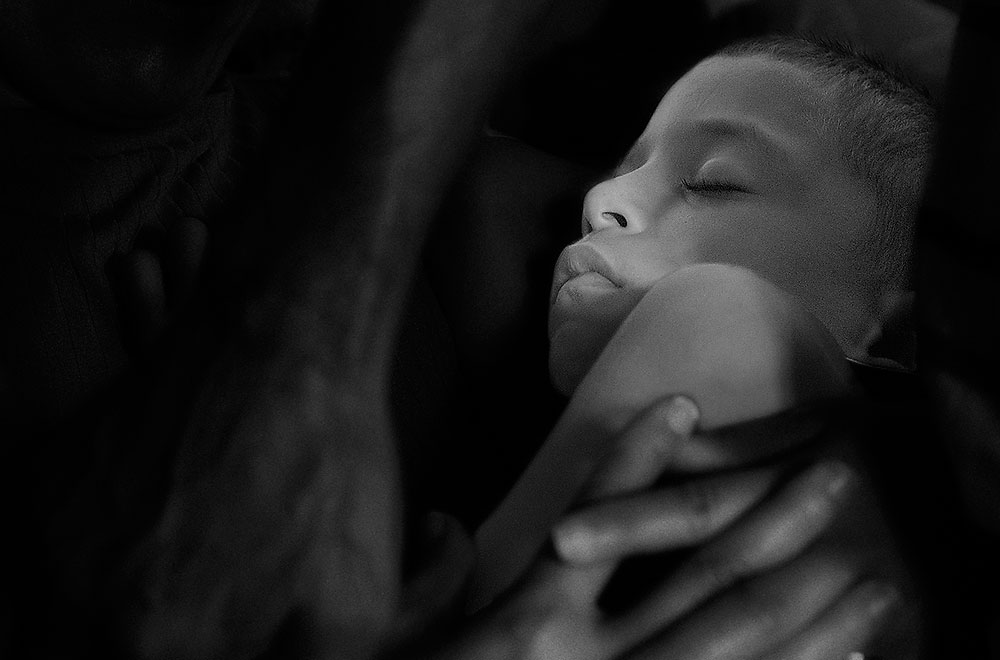

As a 12-year-old youngster in the hospital for surgery he set his sights on becoming a physician. He accomplished that goal when he graduated with his doctorate in medicine from the University of Havana in 1941. Soon after he began residency training at a children’s tuberculosis hospital and acquired research skills in the lab of an allergy clinic, but was disheartened that so many who could not afford specialized treatment went without care.

After his wife died in 1955, Dr. Rodríguez Gavaldá applied for and was accepted into the pediatric residency program at The Brooklyn Hospital in New York. It was there he began to believe in the possibility of opening a hospital in Cuba where he could provide medical care for all children – poor or rich.

The political climate at home was shifting dramatically as he worked and studied in New York. Others in his position might have forsaken the uncertainty of life in Cuba, or even delayed their return, but not this ambitious physician. He had a goal.

“I never thought of not returning (to Cuba),” he later wrote, “stripped of all things social and professional, I am Cuban.”

Perhaps it was the revolution or just his determination and humanitarian sprit, but the hospital of his dreams became a reality in 1960 when he helped found the William Solar University Pediatric Hospital. Soon afterward he established the Allergy and Immunology Laboratory at the hospital where he trained other physicians to help in his quest to treat young allergy patients.

In 1967 Dr. Rodríguez Gavaldá was off to Paris supported by a French Government scholarship to further his education in immunology and brush up on the French language he learned in elementary school. That was a good thing too, because a number of years later he would travel to the French capital after returning from Viet Nam where he served on an international tribunal.

As the years passed the doctor and teacher pressed on with his research and discovered new ways of treating juvenile patients despite the scarcity of many modern pharmaceuticals. And every time he made progress he would present his findings at international medical conferences and introduce them into the curriculum at the University of Havana. It seemed to be a constant cycle of learning, treating, teaching and sharing.

He believes deeply in sharing what he has learned. “Knowledge is world heritage. It would immoral to gain knowledge and prevent the flow of history.”

When we met in 2005, Dr. Rodríguez Gavaldá was the current president of the Cuban Society of Medicine and still treating nearly 200 patients each week. Despite a schedule that would seem grueling for a man half his age, he still finds time to stroll the Malecón, dance and visit with his only daughter at least twice each week.

At the conclusion of our three-hour meeting, Patricia and her father left to return to their separate professions – arm-in-arm physically and mentally.

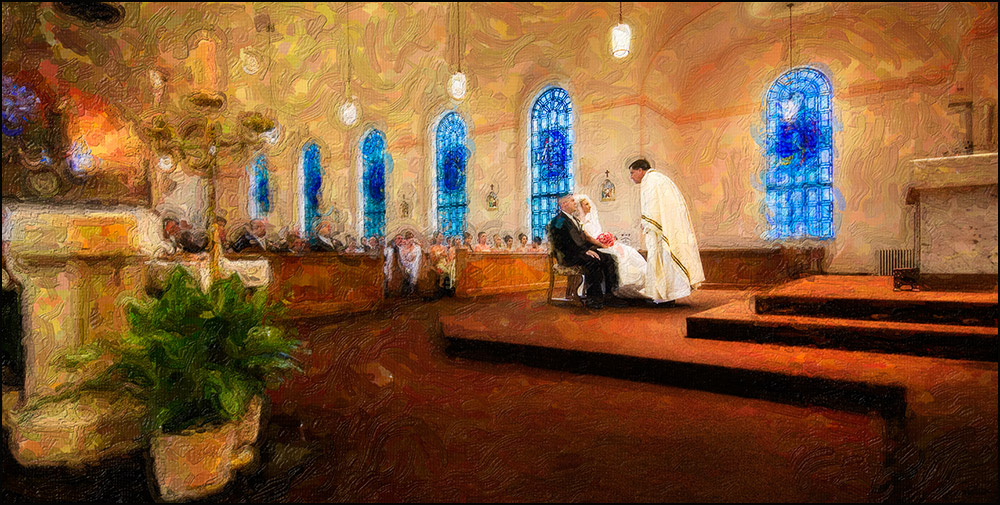

CONTACT ME to order a fine art print of this photograph.